4 Outside the Box Ideas for NBA Teams

From planned vacations to platoons and more, we look at some ideas we'd be curious to see someone experiment with

“Innovation is the ability to see change as an opportunity, not a threat.”

Working at the grassroots and younger levels of basketball, I can tell you first-hand that the game is about to change once again. The Stephen Curry generation of youngsters is becoming high school and college athletes, unabashed about pulling from deep and accustomed to high-volume shooting. Coinciding with those times are big men not jammed down in the low post their entire lives due to their height. They have legitimate skill, handling ability, are encouraged to shoot and can really pass.

The teaching of those skills provides innovative opportunities for college and pro teams in the coming years. The cream rises to the top, meaning the most skilled, biggest players and best shooters now mean positional labels can go even further out the window. The era of size and skill is about to take root.

When we think about innovation, we think a lot about identifying these trends years before they happen. The advantage of doing so is clear: you’re more prepared for ways to embrace that change when it’s been top of mind and you see it coming. So instead of just watching film and applying traits we see to current NBA gameplay and systems, we try to fuse that evaluation with where he think the game of basketball is headed.

Today’s piece is about innovation, but not just innovation from an on-court or skill standpoint. We’ll look at innovation in its relation to how NBA teams are run as a whole. Sometimes that will have to do with on-court tactics and schemes. Other times it’s scouting, or even embracing medical trends and research to stay ahead of the curve. These musings may never work, so please don’t take this as a full 100% endorsement of these ideas as fool-proof strategies. Instead, they are areas I would identify as ones where teams should look into putting these into practice to either test their validity or grapple with the logic behind them.

Here are four outside-the-box innovation-based ideas for NBA franchises over the next several years…

Could an NBA team play a trapping scheme on defense?

Okay… hear me out on this one. A decade ago, the NBA underwent a positional revolution, where the notion of a “power forward” and “shooting guard” went out the window. The lines between positions were blurred, and teams like the Golden State Warriors, Miami Heat and Houston Rockets all trended to go smaller with their rotations, valuing skill over size.

Now in the 2020s, it seems like we’re seeing a return towards size — but with both size and skill present. Players grow up being tall and being asked to play like a guard, giving them fluidity and modern skills that mean there are multiple huge guys on NBA rosters at a time who can play like a guard. Just in the last few years, we’ve seen prospects like Victor Wembanyama, Paolo Banchero, Chet Holmgren, Evan Mobley, Scottie Barnes and Franz Wagner all combine legitimate height with skill rarely seen at their size. Teams are starting to assemble rosters where everyone is long/ big for their position; the Toronto Raptors played a postseason lineup where everyone on the floor had a 7’0” wingspan!

If the NBA is trending in this direction, it means opening up playbooks and major skill advancements across the board on offense. I keep thinking a lot about how defenses will counter that trend. Will they play more zone to utilize their length? Will there be more switching at the point of attack to negate advantages and force isolation jumpers?

One potential gameplan within a lineup that is filled with length is to trap more on the defensive end. Trap ball screens or handoff, run-and-jump star players on the catch, trap anything in the post automatically… just turn up the intensity. With that amount of length on the defensive end, putting two on the ball can make it really hard to pass out of a good trap. The fluidity and movement patterns of bigs nowadays can prevent guards from simply dribbling around them.

On the back side, there’s enough length to cover ground with the other three defenders. They can alter shots at the rim, quickly recover to shooters with impactful closeouts, or even gamble in passing lanes when defensive passers seek immediate help.

Far too often we’ve seen this idea of length equaling switchability without consideration for other schemes. Switching is a very passive strategy on its face; it dares teams to beat them from the perimeter but is not designed to ultimately speed up or make ball handlers uncomfortable. Trapping is a much more aggressive scheme that could lead to increased transition.

We’re probably a few years away from the league bolstering enough talent at this size for multiple teams to utilize such a strategy. Some other teams who are ahead of the curve 1 thru 5, such as Oklahoma City or Toronto, could overwhelm if they move in this direction.

Could we see a team experiment with playing two platoon lineups?

Back in the 2014-15 season, we saw John Calipari of the Kentucky Wildcats briefly experiment with a platoon system. He had such a loaded roster that he decided to let cohesion grow in two separate groups, which he called the “blue” and the “white” platoons. One would start and stay (for the most part) as a 5-man unit. A few minutes later after getting their run, the next platoon would sub in.

Those Wildcats finished the season 38-1, losing in the Final Four to Wisconsin, and had 9 players on their roster go on to play in the NBA. The circumstances with their depth of talent almost necessitated such a system, where no player logged more than 26 minutes per game and ten guys got at least 10 minutes a night. There are merits to the system even for non-powerhouse teams like that, and it’s had some success at lower levels of basketball.

Could something like this work in the NBA? There are certainly obstacles. The league is star-driven, and the idea of having any platoon means spreading the minutes out in a more egalitarian way. Star players would then be on the floor less (unless staggered) and/ or throw off the platoon format. The politics of who starts is always difficult, especially when many awards and financial incentives get tied to minutes played or started.

Over the course of an 82-game season, injuries also threaten the success of a platoon more than they might in college. The season is twice as long, opening itself up to players bouncing in and out of the platoons. You need ten healthy, well-fitting guys to make the platoon work. One injury to the wrong piece and the entire system can be thrown off.

The amount of depth that would be required to win in such a system is also hard to fathom. If it were to be captured by a team, it likely wouldn’t last long, as the salary cap would create hard choices for who to pay and keep among the group. The cap acts almost like a divider of elite and non-elite guys, and minutes tend to follow suit.

We’ve seen versions of platoons emerge on NBA teams before. The San Antonio Spurs tried it on a road trip back in 2015; their goal was to avoid overloading minutes to players in a short time span, and they were missing their best player in Kawhi Leonard. The mid-2010s Denver Nuggets were built on their depth and often played only Ty Lawson over 32 minutes a night. Small versions of the same idea, but not a platoon implemented in full force.

Getting player buy-in would be tricky. Winning games could prove just as difficult. However, the concept could keep players fresh throughout the season, help build leads during times when other groups typically play all-bench lineups, and create ways to maximize every piece of the roster. It’s an interesting idea in concept that likely wouldn’t be too successful over the long run.

Is there any merit to a team giving its players a 3-5 day vacation during the regular season?

One of the most appealing ideas of a platoon system is to save players’ bodies from playing heavy minutes in the regular season. So many teams have gone down the “DNP — Rest” rabbit hole over the last several years; it may be controversial, but there is good reason for teams to do it. Sports science developments indicate the need for rest during the season and for not over-taxing some players.

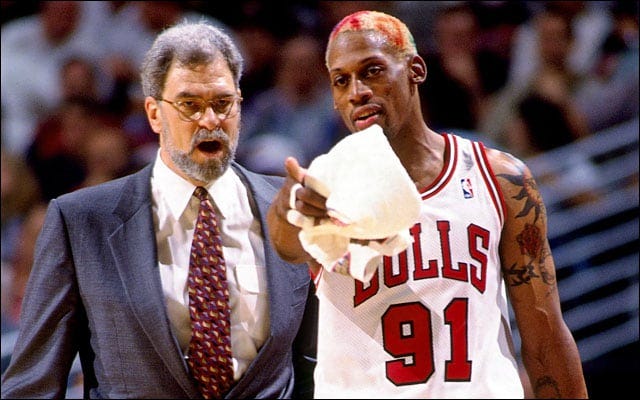

Back in the 1990s, Chicago Bulls head coach Phil Jackson was innovative for the ways he handled interpersonal relations on the team. Dennis Rodman, his most unique personality and player, required something different. The Last Dance documented the time when Jackson sent Dennis Rodman off on a mini-vacation during the season to get away from the team, theorizing that a little time away would keep his mind engaged and buying in for what the group needed.

Could that be a viable strategy across the board?

We’ve been thinking about the idea of coaches sending one player at a time away for perhaps 3-5 days, giving them a team vacation. They miss 1-3 games, recharge their batteries with some family time, rest their legs to stay or get healthy, and then return (hopefully) rejuvenated to help the team. During the doldrums of January, the hectic period leading up to the trade deadline or the beginning period of March, a coach could get away with sending 3-5 guys away on vacations one at a time.

Equity is an issue here, as is injury. Could a coach call his player on vacation and say “we need you to come back” if there are injury concerns? Would the cumulative effect of losing 15-20 games of the full core together have cohesion effects, let alone lessening the power of each team to win games in the interim? It’s a delicate balance, as the indispensable players are the ones who might need the time away most from a health and rest standpoint.

Of all the ideas thrown out here, this is the one we’d be most likely to give a try. Instead of sitting a player for a few days for rest, we’d send him home for a small vacation. Publicly, we excuse it as being away for “personal reasons”. The player can head home, go to a beach somewhere and relax, or do whatever they need to take a brief break. The All-Star Weekend (especially for All-Stars) isn’t really much of a break, and these players tend to breeze through holidays which typically refresh the rest of us.

There will always be those who believe a contract is for 82 games and the players must show up for their teammates, or that the fans are owed full participation. Within a locker room culture that simultaneously is concerned with winning playoff basketball games and valuing the health of the players within the organization, the benefits could outweigh some of those perceived drawbacks.

Should NBA front offices shift scouting departments to virtual work?

The pandemic changed a lot with how businesses in general are run. Work-from-home opportunities are more prevalent and less frowned upon than before. Businesses see the merits in not paying for as much travel from their employees, and productivity hasn’t decreased in many ways.

Perhaps the college scouting world within NBA circles is ripe for an overhaul to trend towards more at-home work. With NBA teams building their own statistical databases, making those accessible through online login is also going to mean scouts miss very little when it comes to metrics. The access to film through programs like Synergy can give scouts plenty of time to watch game tape and analyze it — in fact, each scout can watch much more tape because they aren’t spending their time in airports and hotels traveling.

Franchises can save money on travel and still have productive employees if they are willing to give up the old “got to see them in person” trope. There can still be traveling scouts, just not in as much volume as before. The cuts to the budget of travel expenses can help fund more scouts, too. While I see the value in being at games in person and have found some incredibly valuable tidbits by being there, the difference between in-person and film-based scouting isn’t as large as you might think.

To me, this is a change that can take place in NBA front offices: more scouts, fewer travel, and it doesn’t matter where they live. Have them come into team offices or travel for a select few instances: combines, team workouts at the facilities, meetings leading up to the draft… but not on the road for the entirety of the year.