Ausar Thompson: 2023 NBA Draft Scouting Report

The less heralded of the Overtime Elite twins, Ausar combines rare athletic tools with great basketball sense. Figuring him out is still a tough task

After four years as a college coach, I made a return to the high school level for my first head coaching job in 2021. After a relatively short time away, I’d noticed the landscape in high school athletics had changed. So many more kids, at a young age, were specializing in sports, working with trainers outside of school, and families were throwing money toward skill development like never before.

As a former three-sport athlete in high school, my philosophical opposition to the trend is clear. But more troubling as a coach is the growing sense from families that, just because their son works hard and is in the gym a lot, he deserves a scholarship to college or a greater role on his current team.

Hard work does not guarantee success. Nor does being a good person. But without either, success is nearly impossible to come by. Instead of viewing those as a prerequisite to goal-chasing, too many nowadays see those traits as the meal ticket itself.

‘But Coach Spins, why are you going on a diatribe about the state of high school athletics at the start of your Ausar Thompson scouting report? Are you saying he isn’t going to be successful?’

Not at all. Instead, we’re providing a cautionary tale, one based on the parallels that are evident to us between lauding effort and being naive to the other factors that lead to success. You see, whenever we hear about Ausar Thompson as a pro, the same quips are often thrown out.

He’s got great natural tools to rely on.

He’s a really hard worker and he wants this badly.

He’s a great kid with a tremendous basketball IQ.

To believe that success will come to Ausar simply because of those traits would be, in my estimation, an error. There are plenty of smart, athletic, high-character pros who don’t stick in the NBA… even if they’re drafted rather high and have superstar potential coming into the league. They are great traits that we value, but they cannot be the reason for success.

All we’ve ever encountered with Ausar is a belief from others that he has a supremely high floor. I’m not an Ausar Thompson skeptic, but after going back and watching all the OTE games from this season, I’m not willing to believe that as a blanket statement. There are some real challenges to projecting Ausar’s fit at the NBA level right now.

Let’s get the juicy stuff out of the way early: he’s still a lottery talent and, when all is said and done, could be a top-ten guy on our board. But we do have some questions about the conventional commentary surrounding Ausar: that he’s a high-floor prospect, or that the jump shot is progressing at a believable rate.

I love the intangibles, the character, and the tools… but if I’m going to tell my players that those aren’t a guarantee of success, I have to do the same here. At the end of the day, Ausar will have to produce. And when trying to envision where that production comes from, I have some real questions about how and where he produces.

So much of nailing the Ausar evaluation is dependent on getting an accurate grasp for what we see in the Overtime Elite program. Figuring out where to slot Ausar on a big board is really about confidence: we can see the tools, but are we more confident in selecting him or projecting his success than with Player X or Player Y? The inherent lack of trust in OTE adds an interesting curveball and wrinkle for an already fascinating prospect.

Offense (and the OTE Experience)

Quite frankly, evaluating the Overtime Elite program is a challenge. Just two years into their league, scouts have no comparison points for levels of talent, what to expect from alumni who enter professional leagues, or what the statistics should bear out over the course of their season. Talent and size are apparent, as it feels a lot like a high school All-Star game with moments of real competitiveness and skill. But floor spacing isn’t a forte of the program, as there are very few reliable 3-point shooters.

We’ve spent almost as much time trying to evaluate the level of play as we have the Thompson Twins. For reference, the City Reapers team that both Thompson Twins play on spent 29.4% of their possessions in transition; the average college or NBA team is at about 16%. We’ve been asking ourselves the question for months: is that a byproduct of the level or the result of having both Thompson Twins, dominant athletes and dynamic defenders at their level, who force tempo to raise?

Other OTE teams like the YNG Dreamerz (24%) and Cold Hearts (29.5%) were also in transition a lot. The percentages feel less like a result of the Twins (even if they’re prone to play in the open floor a lot) and more like the up-and-down nature of the OTE program.

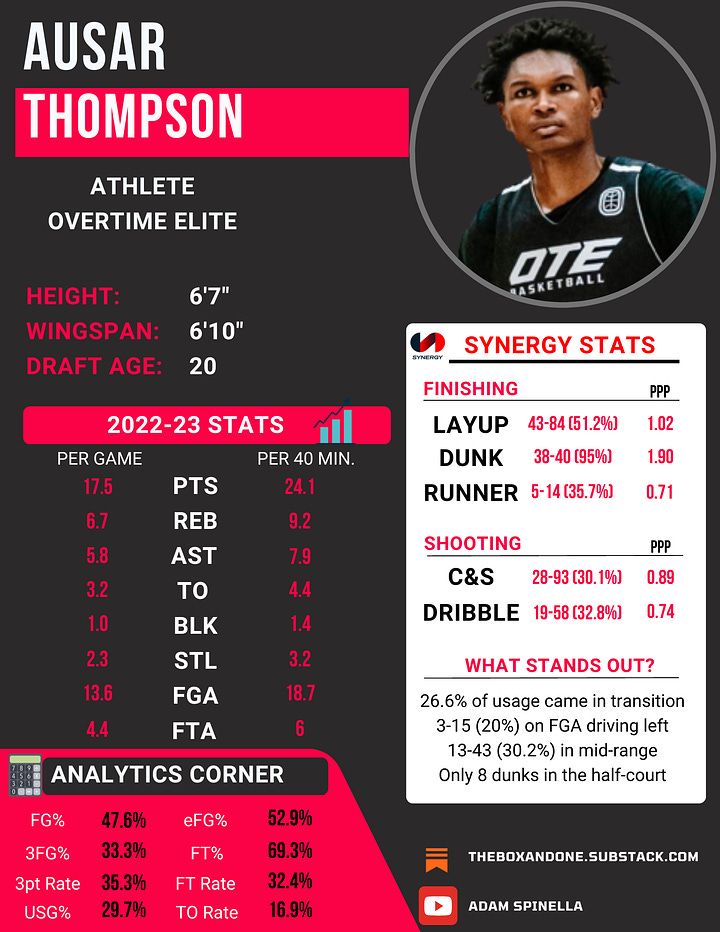

The Thompson Twins are both special athletes who have popped in transition. Ausar has seen 26.6% of his overall possessions come from the play type, according to Synergy, and averages 5.3 points per game from pushing tempo. Any set of highlights can reveal just how damaging he is: a strong handler and rim-attacker when he gets his momentum to the rim, an elite hit-ahead passer with true accuracy, and a guy who scored off breakaway after breakaway.

We feel it more prudent to pivot toward the half-court production to get a feel for Ausar’s NBA impact. After all, if the style of play metrics are any indication, he’ll see his open floor possessions cut about in half as soon as he enters the league.

But there are issues with blindly focusing on the numbers or metrics here, too. The OTE program only had four players take more than one 3-point attempt per game while shooting above 34% from deep. The Reapers shot 34% as a team on catch-and-shoot looks in the half-court; the YNG Dreamerz and Cold Hearts were both under 30%.

It’s plausible that increased spacing will only help the Twins on the offensive end of the floor, and many of the issues we’ve noticed could be eradicated. But what we have noticed is some less-than-stellar half-court production from Ausar on offense in a way that needs to be discussed.

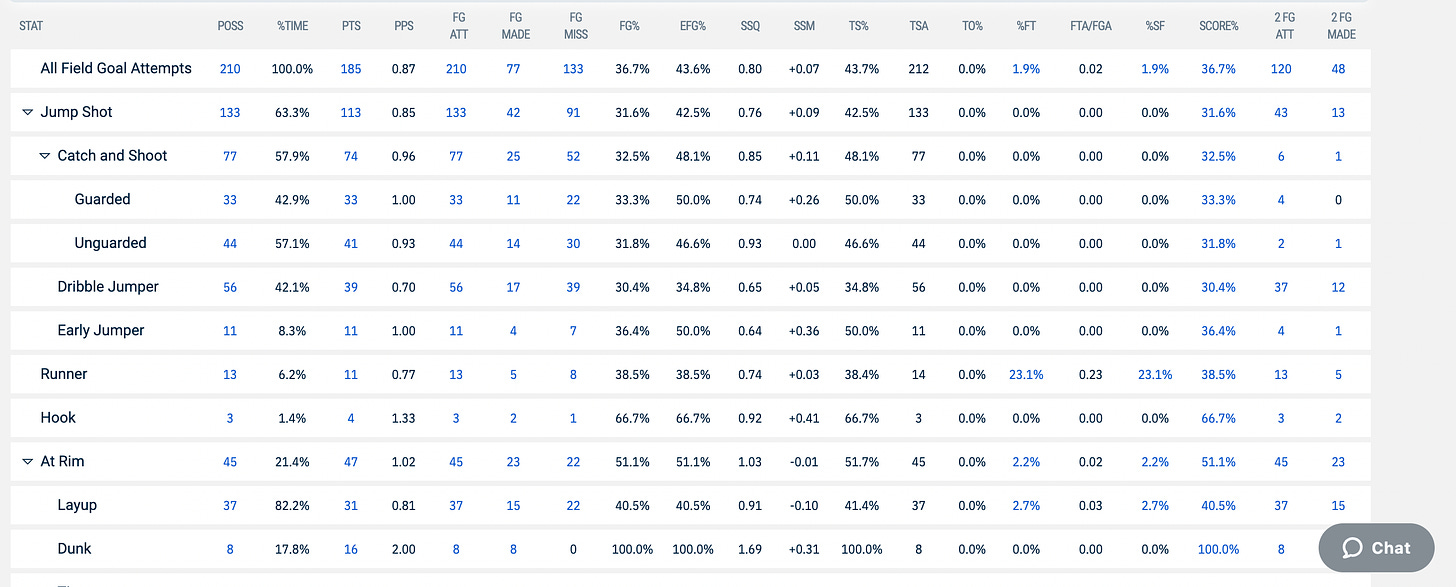

On the whole, Ausar shot 36.7% on all field goal attempts in the half-court, with an eFG% of 43.6%. After a concerning lack of conversion to start the season, Ausar’s rim finishing numbers crept to a really high level. It’s the absence of a runner, the inefficient dribble pull-up, and the below-average catch-and-shoot numbers that really drag him down.

The challenging part of the eval with Ausar is in projecting whether his shot distribution will change at the NBA level. Floor spacing could be a valid excuse for why 63% of his field goal attempts were jump shots and only 21.4% came at the rim. So could the fact he shared the floor with his twin brother Amen, another non-shooting, ball-dominant slasher. But an increase in athleticism at the point of attack, better interior defenders, and sagged-off defense could keep the numbers closer to where they are now.

The best tool we have for figuring Ausar out is the film. As a driver, so many of even his half-court rim attempts come in what we’d deem semi-transition. He’ll have a head start to get downhill, or the defense will still be matching up and not positionally sound.

His burst going to his right is pretty strong, and he does convert at the basket. But it’s the last clip in the video below that stands out the most: driving past a defender who is sagged off.

We know Ausar isn’t a great shooter just by looking at the numbers, and he gets guarded as such. Defenses clog the lane against him (especially helping off of Amen) and try to turn him into a jump shooter or passer. But he’s a phenomenal passer, and his playmaking ability is so strong that he deserves some role at the next level with the ball in his hands. Envisioning him as a ball screen creator isn’t that difficult to do.

There are some biomechanical questions we have for Ausar, and if we were seeing him in pre-draft workouts, we’d want to test them or put him in situations to functionally show us if they’re an issue. One such question revolves around his ability to really adjust to what the defense gives him. It feels like once Ausar gathers to go into a move to score or pass, he’s unable to improvise and change his tune if the original plan is foiled.

We see a lot of half-hearted attempts through contact with less vertical burst than you’d expect from a so-called elite athlete. We see him struggle to adjust to the defense when leaving his feet to make jump passes, not floating in the air for as long as we’d think and sending the ball directly to his opponent.

Ausar is not very twitchy with the ball in his hands. He doesn’t have great deceleration traits once he gets going, and it takes him a step or two to load up and shift into high gear. There isn’t much reactive about him once he enters the lane, and he tends to play at two varying paces as a result: super fast (to outrun his primary defender) or measured or slow (to probe the help defense).

Guys like Ausar who struggle to improvise on the interior tend to be more measured and calculated as passers. Speed causes a loss of control, so they compensate by playing a very controlled style. An indicator of that desire is what I refer to as the decision point, an area where ball screen initiators make their decision as to whether they’ll come off to score or pass. The best players can keep their dribble alive and be a threat to elongate that decision, meaning the point comes as they get closer to the basket. Shiftiness, athletic fluidity, changing-of-speeds, and being a threat to score in a multitude of ways (layup, dunk, runner, pull-up, step-back, or pass for others) all contribute to delaying a decision point.

Right now, Ausar’s decision-point is really early. He is a sensational passer with a really high basketball IQ. You’ll see that in the reads he makes and how quickly he delivers strikes to his rollers. But he has a tendency, even in those positive possessions, to pick up his dribble at or above the free throw line. One dribble off a screen and he freezes to read the defense, puts the ball above his head, and snaps a pass off to a teammate before he even enters the lane:

Because Ausar is tall for a lead guard (6’7” with long arms) he can see over the top of defenses and dissect the right decision. His processing speed is quick, and he creates open looks for his teammates. With increased spacing and more 3-point shooting around him, the assist numbers in ball screens could skyrocket.

But he’s still not driving as a threat to score in any of the clips above. He’s very upright, he’s not guarded like a threat, and the high decision point doesn’t force much rotation from the defense. It’s likely that he’ll need a major roll threat to play with if ball screens are in his future.

We’ve evaluated other players with high decision points before. The most successful one who comes to mind is Tyrese Haliburton. Our analysis of his time at Iowa State was very much the same: somewhat upright, doesn’t drive to score every time, and snaps his passes before entering the lane. Haliburton has figured out impact because he’s so smart. He’s become a great jump passer (shout out Caitlin Cooper), but Haliburton has improved as a pull-up scoring threat more than any prospect we’ve evaluated over the last six years. He feels a lot more like the exception to the rule.

If Ausar isn’t going to be blazingly quick off the bounce when operating in ball screens, he needs a credible pull-up jumper. He went 17-56 (30.4%) on half-court pull-ups this year and had a lot of space to get his shots off. Ausar was played throughout the year like a non-shooter, with teams practically begging him to take the shot:

The early decision point out of ball screens becomes rendered inert if teams go underneath the pick. Ausar will pick up his dribble above the free throw line and survey the floor to see the open man, only to find that the open guy is him. It’s a strategy that really thwarted Ausar and the City Reapers quite often, and one of the reasons why increased spacing isn’t the key to Ausar’s playmaking seeing an uptick, but his overall scoring ability.

Particularly in the mid-range, Ausar struggles to score over contests. There is some evidence of mechanics he can work with, though the pull-up does feel rather two-motion at times (high jump, then gather and release). The result is many flat, line-drive shots that have little touch to rattle in. His hips are good, his footwork somewhat inconsistent, and he very much favors going to his right.

To call Ausar a hopeless shooter would be a gross mischaracterization. His willingness to shoot in this range is an indicator enough of potential. There are plenty of college prospects who get drafted with these types of numbers, and several who avoid pull-up jumpers altogether. The shot just feels very consequential for Ausar’s playstyle, particularly if he hopes to have the ball in his hands at the NBA level.

The mechanics on the jumper have started to take a step forward from a catch-and-shoot standpoint. Ausar was the hero of the playoffs for the City Reapers and shot 38.9% from 3-point range across their sample. Almost all his makes were of the catch-and-shoot variety, with an increase in rhythm and fluidity off the catch. He was still very square and left open (nobody will be chasing him off the line anytime soon), but growth is noteworthy and a great indicator that there is some touch to his game.

Still, it is difficult to throw out the entirety of the sample, which was pretty poor at the start of the year. While Ausar was 12-30 (40%) on catch-and-shoot jumpers in the playoffs, he started the season 13-47 (27.7%), an abysmal mark. Even when wide open and asked to shoot, Ausar hesitated and needed to gather before deciding that his mechanics were in place.

Shooting progression within a single season can be so difficult and oftentimes misleading. We all want prospects to follow the uplifting narrative: the numbers increase throughout the season, it’s due to improvement, and that improvement is sustainable and projectable moving forward. But we all know shooting peaks and valleys happen throughout a basketball season. To call a hot stretch during the playoffs definitive proof of shooting improvement is a little too brazen for me, and could be irresponsible if Ausar’s evaluation becomes tethered to this six-game improvement.

If it feels like we’re focusing on the negatives, it’s because there are some glaring holes in Ausar’s game. But what we’re going over is more about the functional ways to utilize his skills in the half-court. If he doesn’t get to the rim a ton off the bounce, isn’t a pull-up threat, and is a questionable shooter off-ball, where does his impact come from?

The jump shot is so much more important to Ausar than it is to Amen, and might be more important for him than any guard in this class. Ausar has an incredibly high basketball IQ, supremely good passing feel, and incredible touch around the rim. Without being a threat to score in the mid-range, his passing reads will be somewhat locked as teams don’t collapse on drives. If opponents go under ball screens, he’s not getting to the rim to use his touch. If nobody closes out to his catch-and-shoot looks, attacking closeouts and getting into the lane to harness all his skills won’t happen.

There are ways we can see Ausar making a positive impact anyways. The first is as a cutter. Ausar is, at least to this point of our dive into the class, the best cutter in 2023. He’s so smart about when to go, feels slips and backdoors instantly, cuts violently, and has the explosion to finish above the rim when he gets there. He’s going to find ways to be productive off-ball.

He’s also able to use his elite basketball IQ within the flor of offense. He’s a great connective tissue passer, which is why his impact doesn’t solely hinge upon scoring ability.

A creative coach or scheme can put Ausar in so many different areas to make an impact. He’d be great as a short roll passer, setting screens for other scorers atop the key. He’s awesome at the elbows facilitating within set plays, and especially dangerous curling off screens — even if his man goes under.

Defense

Much like on the offensive end, there are a few biomechanical questions about Ausar that we’d want to get answered. These feel much more correctable on defense and, in my opinion, are driven by effort and consistency more than by ability. Ausar comes out of his stance a lot — it’s a common high school habit that, unfortunately, I’ve seen first-hand in my years as a coach.

When Ausar is down in a stance and engaged, he’s a wildly disruptive on-ball defender. We can see him successfully guarding 1 thru 3 in the NBA, with his best role as a pest against opposing handlers. Ausar loves to pressure at half-court or beyond and really get into the basketball. If he’s quick and engaged, good athletes have a difficult time getting separation from him.

His first step laterally is pretty impressive.

Ausar is a tremendous help defender, too. He’ll be one of the better rim protectors as a wing, at least in terms of weak-side rotations. He does gamble a fair amount (again, a byproduct of the Overtime Elite system) and shoots the gap for passing lane steals a lot. His athleticism and ability to create in transition are too great to dampen those instincts, though. He should be given a somewhat free reign.

Where Ausar needs the most work is in staying low and being better at the point of attack consistently. He can be a tad jumpy, reactive to jabs or crossovers, which create separation. He likes to crowd the basketball, which can get him into less-athletic positions or even standing up in general.

If Ausar is going to defend opposing 1s and guard at the point-of-attack primarily, he's going to need to be better at getting through screens. He gets easily bumped and doesn’t play low enough to recover. The length can help him contest from behind, but right now he’s not even in the rearview mirror when pull-up jumpers take shots off a pick.

Ausar’s defensive potential is sky-high. Few prospects have his natural tools, IQ, or positional versatility. A few smaller tweaks can turn him into a wildly impactful on-ball stopper.

Overall Analysis

At the beginning, we touched on the idea of Ausar being a high-floor prospect. I don’t exactly find that to be the case. In comparison to his twin brother Amen, who is a much riskier boom-or-bust type based on his play style, Ausar comes off as the higher-floor of the two. But having a higher floor than someone else doesn’t make someone a low-risk player on its own.

There are two rules I try to live by when doing NBA Draft scouting:

Envision a role that fits with what I’d want to build. Some players may be really good but not fit into the role that I prefer for my desired style of roster construction.

Place myself in the role of the general manager of a team. Would I put my job on the line for this kid? As a person, as a player… will taking him potentially get me fired, and can I stomach the risk or defend why I’ve tethered my job to this kid?

The first is very important to me. Plenty of good prospects have been lower on my overall board because, quite frankly, I wouldn’t want to commit my roster to playing their style of basketball. Most often, that refers to guys who are inflexible positionally (small guards, for example), have major deficiencies that require schematic catering to offset, or are playstyle hijackers who need the ball or need to be put in certain positions to succeed.

Ausar does not strike me as any of them. He’s versatile positionally (especially on defense), has enough connective tissue DNA to make a positive impact in different offensive spots, and doesn’t need to be blanketed or protected by schemes. But there are still fit issues that we’re aware of, at least when trying to answer whether we’d prefer to have Ausar than some other lottery hopefuls. Because let’s be clear: Ausar is a lottery talent with all the tools he brings and what he’s shown thus far.

Fit is going to be so important for him. Can he play next to a vertical lob threat so pick-and-roll reps have a chance to succeed? Can he be surrounded by 3-point shooting? Will the coaching staff be able to identify and correct some of his shooting deficiencies? Will he be asked to be more of an on-ball or an off-ball player?

The other questions are ones that are impossible to predict or cater for to a certainty. Will the catch-and-shoot progression we saw down the stretch of the season stick? Can he get better as a pull-up scorer? Will he learn to play at multiple speeds and, therefore, become a dynamic attacker with the ball in his hands?

There’s a lot that would need to go right for Ausar to become a primary option at the next level, and still some work that needs to go into becoming a reliable off-ball option. Valuing him in the mid-to-late lottery, where he can be fine as a connective piece, is where we’re at right now.

But there’s something endearing about a high-feel athlete who is a hard worker. This evaluation isn’t a bet against Ausar, just an admittance that all the questions around the OTE program and its translation to the NBA make it more difficult for me to stick my neck out and tether my job security to what we’ve seen thus far from Ausar… at least closer to the top of this draft class.

Loved this one, Coach. I especially enjoyed the two criteria of evaluation. For me, I can’t help but think about where the league is going - does this player project well based on how the league is trending. It’s getting harder to keep undersized guards out there, to your point. Oversized, high-IQ players who can not only be effective on both sides of the ball but create advantage - that last part I about a lot. The Thompson twins tend to check those boxes more than some other lottery prospects. Very polarizing!

This was an awesome writeup, Adam!