Is Free Throw Success an Indication of Shooting Upside?

A common trope in the draft community, the link between free throw touch and becoming an above-average 3-point shooter is sketchy at best

Summers are awesome. During the downtime in August, we try to spend a lot of our time diving into philosophy and think-pieces with the aim of getting better for the upcoming draft cycle. Sometimes those studies are data-driven and involve a statistical look at indicators for NBA success. Other times, like last week, they look more at what it means to be a winning player, and if there’s any merit to such a claim.

This week, we’re diving into a topic that has long been a point of frustration for us and we’ve been opposed to: the notion that free throw shooting can translate to success from 3-point range.

Now that we’re entering our sixth draft cycle, we’ve confidently heard this idea applied to at least a dozen prospects. So many of us scouts are spending time trying to figure out who can add certain skills as an NBA player that they don’t already showcase pre-draft. Shooting is often one of the most important in today’s game and has become vital for role players. As such, scouts spend a lot of time looking at shooting form and other factors to try and predict if a player who currently doesn’t shoot the 3-pointer effectively will be able to.

Time and time again, what we hear as a litmus test is free throw percentage. If a prospect is a good shooter from the line, it is indicative of touch, and therefore that touch can be harnessed into jump shooting impact.

We’ve never subscribed to that theory. The muscle memory that goes into a free throw and the repetition that goes into jump shooting are drastically different processes. So we set out to try and prove ourselves right, to test our hypothesis with a statistical study. We decided to look at players who have been drafted that met those criteria as good free throw shooters but poor 3-point shooters, and would then see if there was any merit to the claim that it was an indication of shooting potential.

There are some filters within this study in order to get consistent data. First, we are looking only at college players and prospects, not international ones. Second, we’ll spend a heavy focus looking at drafted prospects, not undrafted free agents or signings. Third, there will be some prospects who met these criteria in collegiate seasons other than the one before they were drafted. If the improvement already took place in college, it would make the study about how to identify these shooting improvements before they happen a moot point.

We need to find some statistical filters to identify prospects by. Because this is about free throw shooting, we need to start with a pre-draft filter that would indicate strong touch from the line. We consulted with several scouts to see what they considered being a “good” free throw shooter to be, and making two-of-three from the stripe was a common answer. Thus, our free throw percentage indicator was set to 67%. We also decided to go with an arbitrary point to help sift out any small sample sizes from the charity stripe: 50 free throw makes were required to give confidence that the shooting touch at the line is legitimate.

If we’re looking for improvement, we also need to find a starting point (college percentage) that is low enough to be considered poor and an ending point (NBA percentage) that would see improvement. Again, after consulting with a few scouts, the 30% mark was what was mentioned as a potential litmus test. If a prospect knocks down north of the 30% mark pre-draft, they likely show enough promise to be seen as a potential shooter.

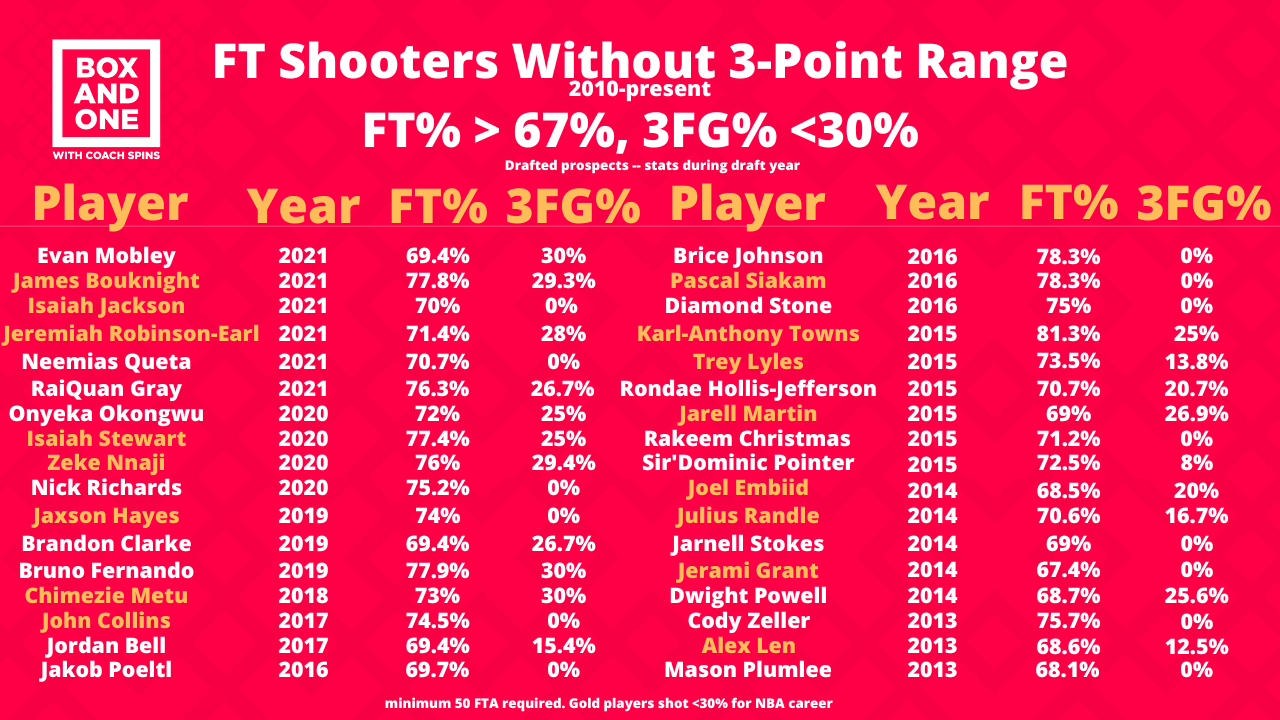

Below are the results of the query, run on Barttorvik, starting from back in 2010.

There have been 55 drafted players since 2010 (not counting 2022s, who haven’t played NBA minutes yet) to shoot over 67% from the free throw line and under 30% from 3 during their last collegiate season. Of those 55, 21 of them (38%) have shot above 30% in their pro careers. In fact, 16 of those 21 players have a 3-point attempt rate in the NBA above 20%. The four who do not: Anthony Davis, Julius Randle, Jaxson Hayes, Isaiah Stewart, and Isaiah Jackson. It would seem, then, that those guys with a high free throw percentage in college without dependable 3-point range have around a 1-in-3 chance of adding it to their game. At first glance, it’s a pretty solid indicator.

But as the great Lee Corso would say, “not so fast, my friend…”

Peeling Back the Layers

There are several other factors that go into determining who will reach those benchmarks and why. I refer to those factors as “asked and developed” factors. The first part: is the prospect going to be asked to shoot 3-pointers by their NBA team? There could be other players listed above who are not given the reign to attempt triples on their team but have the latent ability.

In a similar vein, a player may never be asked to develop such a shot because their game is to be focused elsewhere. Saying “one in three who meet these criteria add a jump shot in the pros” may be a tad low of a qualifying statement, because not every player within the query is trying to develop that jumper.

That does assume, however, that many of these guys would have been able to shoot in college if they were capable — that it’s a skill that needs developing, not just unleashing. Karl-Anthony Towns, one of the most prolific big man shooters in NBA history, was only allowed to take eight attempts his lone year at Kentucky. At the time, Towns was widely regarded as a stretch big man coming out of college despite not taking those shots prior to the draft. Others, like Mike Scott, were victims of a poor shooting final season in college; Scott was above 36% from 3 for his five-year career, taking 44 over five years. Mike Muscala had the same collegiate trajectory.

As a result, it’s hard to compare those players (who clearly had the latent skill and simply weren’t asked to do it enough or consistent in their small sample to test out of our thresholds) to guys without any shooting sample. Their presence may unfairly skew the data.

As we looked into the numbers further, we wanted to see if there’s a connection between adding 3-point range and the willingness to shoot them at lower levels. A sensible hypothesis would be that even if the percentages are low, the player’s willingness to take them (or the allowance of a coach to do so) could indicate enough potential to invest.

Of the 55 players to examine here, only nine took at least one 3-point attempt per game during their draft year. Four of those nine (Jeremiah Robinson-Earl, James Bouknight, Chimezie Metu and Jarell Martin) are above the 30% mark for their careers, and the list also includes Evan Mobley (who many believe will shoot it) and Derrick Williams, who barely missed the career threshold.

Take the rest of the numbers and extrapolate them out: 46 players did not attempt one 3-pointer per game, and 17 of those prospects (37%) have shot at above 30% from 3 in the NBA. Perhaps willingness to shoot isn’t much of an indicator. As college coaches are jumping on the 3-point trend and players develop these skills at an earlier age, we may see attempt rates skyrocket, thus changing the data in future iterations of these queries.

Raising the Free Throw Percentage Barometer

Numbers are, however, arbitrary. Who is to choose 67% as a free throw mark for generally being seen as positive? We could raise that number and further filter down the group to see if there’s a shared benchmark of free throw percentage that should be higher.

Only 4 of the 25 NBA shooters were below 70% from the free throw line. 8 of the 25 were above 75% from the free throw line. That mark feels like a much safer one, but is not in reality. Of all the players to shoot 75% or above from the FT line but 30% or under from 3-point range in college, 8 of those 20 (40%) made it to the 30% threshold in the NBA. That’s not much of an improvement on the whole, and if we bring that number to 80%, we only have four qualifiers: Towns, Tyler Zeller, Mike Scott, and JaJuan Johnson.

Raising the 3-Point Percentage Barometer

What if we changed the litmus test for NBA success? 30% is a barely-passable threshold. Is that the goal when identifying talent? A league-average shooter would make 35.4% of their 3-point attempts. What if we rose the criteria from 30% (a general baseline for having enough leash to attempt 3-pointers) to the league-average mark to see if this is predictive of a prospect becoming a good shooter?

Only 7 players would be left. Yes, that means barely one out of every ten players drafted with poor 3pt. numbers and solid free throw shooting turn into a league average or above shooter from deep. Those seven: Meyers Leonard, Mike Scott, Mike Muscala, Karl-Anthony Towns, John Collins, Jaxson Hayes and Zeke Nnaji.

Nnaji and Hayes are early enough in their careers to potentially be small sample size additions; we’d feel more comfortable discussing them once we get more data. Towns, Muscala, Scott, and Leonard all were mentioned pre-draft as ideal floor-spacers; Muscala and Scott showcased that in years prior to their draft declaration. Collins and his shooting development seem more like the exception than the rule. Because this is a piece on macro statistical trends as indicators of future success, we won’t dive into Collins’ improvements on a micro level.

Look back at some pre-draft sentiments around the highlighted players from that list and it shouldn’t be any surprise that they turned into efficient 3-point shooters. Mike Muscala was the best shooter at the 2013 NBA Draft Combine in drill work, and was projected as a pick & pop threat based on his shot and play style. The same can be said for Mike Scott out of Virginia. The big reason Meyers Leonard rose up draft boards is because of a great shooting performance at the combine, as former Blazers executive Ben Falk confirmed. Towns didn’t shoot it at Kentucky, but according to DraftExpress, was shooting them reliably as a 15-year-old and in high school at a high clip — a big reason he was a prolific recruit out of high school.

Even in those responses from draft scouts, free throw shooting comes up. Perhaps the appropriate way to utilize free throw percentages is to confirm what you believe about a shooter’s mechanics and ability to become a strong 3-point threat, not to use as a starting criterion.

Some other players who fell short of the league-average threshold have shown lots of promise. Julius Randle, despite shooting 33.2% from deep for his career, was over 41% from deep on over five attempts a night during his All-Star season in 2021. Joel Embiid is a much better shooter than his career numbers indicate, and he’s been at a lethal 37% each of the last two years (he was also seen as a shooting big man pre-draft).

Guys like Pascal Siakam (32.8% career), Anthony Davis (30.3%), Isaiah Stewart (33%), and Dwight Powell (29.6%) are seen as good enough to shoot them on a semi-regular basis. There was a lot of pre-draft discussion about Stewart’s ability to shoot, and it may become a point of focus for the Detroit Pistons after drafting Jalen Duren. If you watch any of these guys play, they strike little fear in the defense when they shoot jumpers. Part of that is their primary skills being elsewhere (Davis and Siakam are elite driving bigs, for example). Part of it is also that they don’t shoot it well enough to force a defense to take the jump shot away. If that’s the case, then would we really trumpet them around as a success of shooting development post-college?

All in all, what this tells us is that if one of these guys is going to be a really good NBA shooter, you’ll likely know it before the draft. Having success here as a scouting department is more about finding out who can already do it, not seeing who has the teachable traits to add the skill.

Conclusion

This entire study, and anything done with data, is about finding the minimally acceptable threshold for where you would draw the line. For some, that may be at “good enough to shoot them”, in which case, 30% is a solid mark. Two out of every five players who met our query went from south of 30% to north of it in the NBA. To some, that could be seen as a success.

To others, the draft and its returns are about finding above-average impact, not just average impact. And if league average is the minimally-accepted threshold, it’s hard to justify the idea of ‘positive free throw shooting is an indication of future shooting success’ with data. This is the camp we fall into: when you draft, you look for above-average. Without the other context of jump shot form and collegiate role, simply looking at free throw percentage doesn’t inspire confidence in finding an above-average shooter.

Each shooter is different, from their mechanics to their shooting trajectory and their comfort level. But what tends to be bothersome is the blanket statement that gets thrown out about prospects: “they have good touch from the free throw line, an indication they’ll be able to shoot it.” If we’re looking for someone who is good in comparison to the rest of the league, we’re best served to draft someone with a proven shooting track record. To buck that trend, have to feel incredibly secure in the shooting mechanics and background of the individual prospect in question, most likely finding evidence pre-draft that they are a capable shooter already.

Terrific piece, loved the statistics angle to debunking the FT% —> 3P% go-to. Thanks Coach!