The Ten Commandments of NBA Draft Scouting

Resharing an old piece as a reminder for how and where to look through the draft process

This article is a facsimile of an earlier publication on The Basketball Writers (TBW), which recently closed its doors.

When I joined The Basketball Writers, I was excited about entering a space that was craving change to the current landscape of analysis. Most of the free and oversaturated content is structured the same way, designed for heavy clicks—catchy but frequently unsubstantive content and cut from a cloth that the everyday consumer can understand.

Taking highly difficult topics and elegantly explaining them to the masses is an art form completely bulldozed by an instant gratification model that values a simplistic one-size-fits-all approach to analysis.

Perhaps no NBA niche online is more heavily affected by groupthink and over-simplicity than the NBA Draft.

Coverage leading up to the draft sees mock boards all heavily influenced by one or two experts who drive the conversation while offering brief one-or-two sentence bites as to a player's "strength", "weakness" or "upside". We still see antiquated terms such as "power forward" or "center" all over the place, and rarely attempt to color outside those lines. We view the draft as an opportunity to meet the next NBA stars without actually understanding their path, background or previous situation.

We want to provide a few rules and guidelines that help understand some of the most important nuts and bolts of scouting in a modern and changing NBA. Combining a few front office insights I have gained with my own scouting tips learned on the collegiate recruiting trail, here are my so-called Ten Commandments of talent evaluation:

1. A Player’s Position is Determined by Who They Defend

Many scouts or coaches give different answers pertaining to what they label positions as nowadays, although most are in agreement that the old-style labels are antiquated. Boston Celtics head coach Brad Stevens stated nearly two years ago that his team features only three true positions: ball-handlers, wings and bigs. Other iterations of this thought exist, but the shift in thinking is based upon the changes of playstyle.

The problem with the old model (i.e. point guard, shooting guard, power forward, etc.) is that it fails to capture where the game has trended.

Switching is a strength, and labeling someone as a small forward does not accentuate the benefit of having them be able to defend multiple positions. Offenses have valued the three-point shot, opening the lane and rarely featuring two players that only operate with their back to the basket simultaneously. Such a concept has morphed the sense of what a power forward or a center is.

To simplify, teams talk more about positions as existing 1 thru 5, the numerical equivalent that allows for more blurring of skill levels to fit within a style. The numbers are based on height and size, with someone that is a 1 being on the smaller side, while the biggest players on the floor jump to the 5.

But this still fails to capture multi-positional value.

Players like Ben Simmons, Draymond Green, LeBron James and Giannis Antetokounmpo don't really have a true number because their skill portfolio isn't seen typically for someone of their size. In essence, in order to play someone to their strengths, the numbers have to be somewhere between incredibly fluid or meaningless.

Labels and understanding positions is still important, whether it's as simple as finding a "handlers, wings and posts" format or something a little broader. Categories help simplify our mental organization for problem-solving, an exercise that anyone in the league must tackle.

So here's the best way I have found to solve this issue: View positions based on defensive aptitude.

Using the standard 1 thru 5 can be effective for determining how many traditional positions a prospect may be able to guard, but in terms of categorizing them, I utilize six categories that are fluid enough to blend with the modern game:

Point Guard: The traditional "lead guard" that plays with the ball in their hands. Defensively, they cover other smaller players on the court.

Combo Guard: A player without the requisite size to consistently defend players in the wing category and lacking the evidence to be considered a lead ball handler within an offense. Essentially, they are guards that combine the offensive skill of a wing with the defensive strength of a guard.

Wings: Such a fluid category, these are players who are mainly versatile on either end thanks to the league's shift to playing multiple wings at a time. However, wings don't float outside the label to combine more than one skill with other categories. They are too big to be considered a 1, too small to be considered a 5, and have the versatility to fall somewhere between the 2 and 4 based on the lineup.

Forwards: The combination of a wing and a post. Forwards are face-up size players that do not find their strengths in back-to-the-basket play on either end. They also have some skill overlap with a wing, where their defensive strength combines with their versatility to play some at each of the wing and post positions.

Posts: More traditional back-to-the-basket or defensive anchor positions, posts may have the least versatility of each positional group. The main difference between a post and a forward comes from the ability to defend on the perimeter.

Athletes: Players that do not fit precisely into any mold. The "unicorns'" offensive and defensive skill sets are either too versatile to cram into one box or so unique that they require their own unique description.

This style of analysis both blurs lines and creates them, which in my opinion is how scouting processes should be.

The biggest key: no team must have one of each position on the floor in order to be successful. A team of five wings can be successful. Having two combo guards instead of any point guards is a method to success. There is no blueprint for how to combine these positions, just ways to think of them based on their strengths.

2. Do Away with the Term “Weakness”

A wise collegiate coach once taught me the importance of not over-fixating on the phrase "weakness."

"Don't convince yourself of what a player cannot do just because they cannot do it yet," he would say. "A weakness is just an area they haven't shown the time or ability to improve, and until you are certain they have not improved because of ability and not time, it's not conclusively a weakness."

Terminology plays a large role in how we analyze and are open to that concept. For the sake of our scouting department here at The Basketball Writers, we need to do away with the phrase "weakness" and replace it with "improvement area."

It's a glass-half-full mentality that puts the emphasis back on the player and the coaching staff to round out a player's game, and it's such a powerful frame of reference: Just because something isn't visible doesn't mean it isn't there.

Players get harmed by this concept all the time and often are undervalued on draft boards as a result. Some players do not get the opportunity to showcase all their skills before arriving in the NBA, and it's on a scouting department to identify those hidden aptitudes.

The best example lies with the Phoenix Suns and Devin Booker, who, coming into the draft process, was labeled as a weak offensive creator. There's a reason for that: His usage at Kentucky. Booker was only used as a ball handler in the pick-and-roll on 2.3 percent of his offensive possessions in college, according to Synergy. Yet, he finished this season with 34.5 percent of his offense coming from ball screens and another 12.5 percent in isolation. He created for himself on nearly half his offensive production, breaking that pre-draft mold that he was "predominantly a jump shooter".

The scouting department in Phoenix was able to unearth this upside as a playmaker—perhaps some of it out of necessity, as the team has lacked any semblance of traditional point guard depth—and now Booker is one of the most heavily-used ball handlers in the NBA.

This leads to the next point...

3. Be Overly Cautious with Player Comparisons

Player comparisons can be the death of prospect evaluation. We have heard in the last two years that the New York Knicks are enamored with a prospect because he reminds them of Paul George. There is so much danger in that comparison.

George is a vastly different player now than he was as a prospect, due in large part to the strides his offensive game and jump shot have taken. But by comparing Cam Reddish, said prospect out of Duke, to the All-Star from the Oklahoma City Thunder, Reddish would almost certainly need to rise to All-Star level in order to live up to the comparison.

We throw the terms floor and ceiling around quite a bit when discussing players based on how close we believe they are to achieving their potential. Trying to target where someone is on their development curve is literally the name of the game, so this is a necessary practice.

However, false senses of expectations and developmental timelines can come to fruiting when the comparison is thrown out there in such a concrete and public manner. Remember, there are two different ways to compare players: play style and overall impact. The issue with doing either is that, once the comparison is made in one area, it will be really difficult to unsee it in the either.

For example, if the Detroit Pistons are on the clock fifth overall and we said “you should take Player X, he’s great, he plays a very similar brand of basketball to Armoni Brooks”, that may get you questioning whether he should go that high. Not because what Brooks does isn’t valuable, but because the first image of comparison in your mind is that of an undrafted free agent.

The same goes the other way. The comparison of “definitely draft Player Z, he reminds me so much of Paul George” means that, even if you’re just focusing on a few similarities in their body types and where they get their points, you start to expect that Player Z will produce on the same tier as the All-Star George has. Player comps raise lofty and often unrealistic expectations, so use them very carefully.

4. Balancing Natural and Learned Skills

NBA coaching staff and front offices are equipped with more resources at their disposal than any basketball league around the globe. The quality of teachers and the depth of their instruction is underappreciated.

In essence, an education to skill development reaches its highest levels while a player is in the league, not before it. So many skills—whether how to play the game correctly, how to improve a jump shot or developing a signature move—are gained after a prospect is drafted.

Those are all learned skills or parts of a player's toolbox that can be imprinted upon them by an outside mentor. A franchise with great confidence in its coaching staff (and veteran player leadership) will trust that the necessary skills to reaching one's potential can be taught in-house. We see a shift to emphasize natural skills through the draft process, things like a vertical leap, wingspan or speed. Yet, those cannot be taught or improved.

As cliche as it sounds, a balance must be found between both.

A player with no learned skills already (who is usually described as being "raw" or a "raw athlete") only has so much upside because time isn't on their side to develop those skills (in time during the length of a "prove it" NBA contract). Players with little in the way of natural talents, despite a high level of skill, may never be able to make an elite impact in such an athletic league.

Finding players with both is the key.

A front office should focus on identifying which learned skills a player does not have yet that their team can teach them. If a strong athlete is not a good shooter yet, what is it about that improvement area and the strength of the organization that can change that narrative?

Think back to Kawhi Leonard, a notoriously subpar shooter at San Diego State. The San Antonio Spurs, with world-renowned shooting coach Chip Engelland, correctly identified that this was not only a skill Leonard was able to learn but one they were able to teach. That marriage is vital, and why the scouting process is meaningless without a long-term plan for helping that prospect improve.

5. Fit is a Two-Way Street

For those same reasons, we have to take a look at the fit between the two parties. Too frequently we think about it from a team perspective.

If the Miami Heat have Hassan Whiteside, who is a true post player, why do they need to draft Bam Adebayo? We tend to think of fit in terms of the path to playing time for the prospect and holes on the roster for the franchise, when in reality fit is as much about the individual.

Do not lose consideration of fit for the player. There are questions that exist which we cannot answer (more on that later) but are absolutely necessary: Does this person fit with our current roster and core? Are they built to live and thrive in our greater community? Can we as an organization bring out their strengths, both with our on-court talent and behind-the-scenes staff?

Fit can be forgotten when only one actor is the decision-maker, like in the draft setting. Prospects have no control of where they end up, so teams tend to view fit only through their lens.

Successful recruiters and evaluators understand that maximizing a player's potential comes when they are in the right environment. The number of players that make a larger impact on a second team or after their rookie contract expires is countless and is most likely due to the improper marriage resulting from the draft process.

6. Don’t Worry About Market Value

I've always believed in one simple concept as a recruiter: If you love a player, go get him. There is a tendency to over-value the consensus of a player and let that dictate whether a college coach will actually give a player a scholarship offer, waiting to see if the rest of the recruiting landscape agrees with their initial assessment.

The NBA Draft is very much the same way to me. We often get too caught up in draft ranges or wonder why a team doesn't trade back to maximize their value. I firmly believe that you should just take the player you want. The worst thing that could happen: trading back with a player in mind, then someone else takes that player. Now, you wind up with a worse draft selection and without the guy you targeted.

That’s why the Phoenix Suns were wise to take Cameron Johnson, a player they felt comfortable in and wanted, in the lottery despite other teams bashing them for it. Getting caught in asset management of trading back or trying to anticipate where others value a player can be a detriment to actually getting the guys you want.

Just take the guy you like and believe in. That’s what the draft is ultimately about.

7. Context is Important, So Learn it

Decision-makers don't just wrestle with what something is, they must seek to understand the why. Context around every prospect is important.

Why did Trae Young have such a high usage rate in comparison to Shai Gilgeous-Alexander? Why did Donovan Mitchell play without the ball in his hands at Louisville? Why did Devin Booker only be utilized as a pick-and-roll ball handler on rare occasions?

The answers to these questions—and challenging the common conception with the question why—is what unearths gems or provides important context in evaluation.

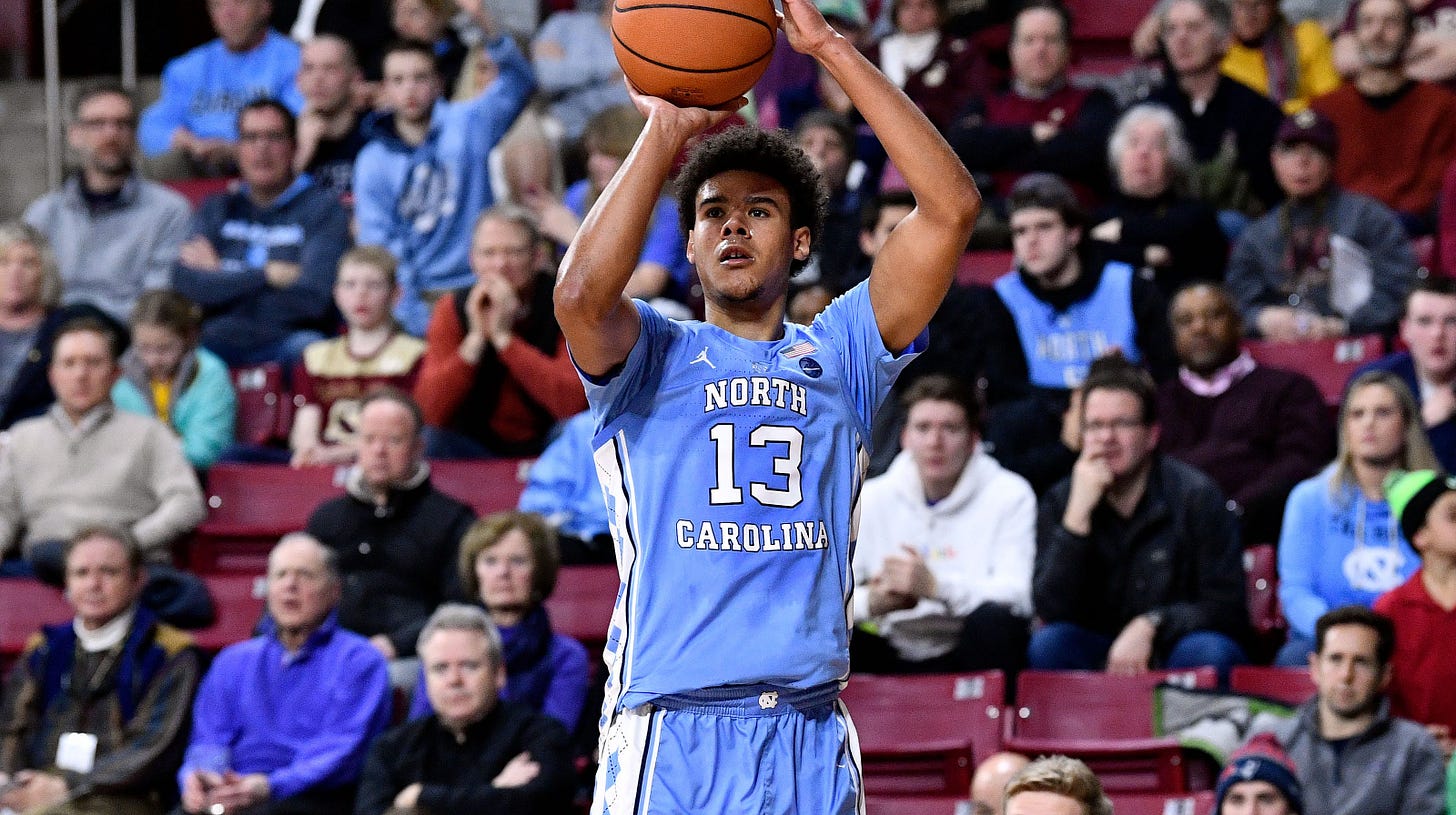

That extends beyond skill set but also into statistics. Players that come from the University of Virginia, one of the slowest-paced teams in the country, will have a vastly different statistical profile than those from the University of North Carolina, which plays at one of the fastest tempos in college. They also run different offenses, where a lead guard at Carolina will have greater assist numbers than one at Virginia, which runs a true motion and rarely scripts ball screens for its players.

Does that mean the Carolina player—who has both the experience as a pick-and-roll point guard and a statistical portfolio that boosts his resume—is a better prospect than the one from Virginia? Of course not. All it means is that we must unpack the context to understand why the visuals around their trajectory are so different. While the Carolina-Virginia example is a simplistic one, scouting departments act like private investigators because they're concerned with a player's ‘why’, not just their ‘what’.

8. Understand the Value of Age

A first-round draft pick is a four-year commitment from an NBA team. If all goes according to plan, they re-sign that player for either a four or five-year extension, now locking up their franchise pillar to become one of the highest players on their payroll.

All of a sudden, eight or nine years go by, and as that player is ready to ink their third contract, their Bird rights are incredibly important.

No team enters the draft thinking they will fail to unearth their next franchise pillar; Such a defeatist attitude would indicate a team shouldn't make the selection at all and is better suited to trade their pick. They all believe they have found a long-term commitment.

The starting age of a draft prospect plays a huge role in determining where they are selected partially due to that long-term contractual outlook. If a player is drafted at 19 years old, they finish their rookie contract at 23. The aforementioned four-year extension would run until they are 27, still firmly in their prime to sign another long-term deal for their third contract. Now the franchise gets around twelve years of a player in their prime.

But consider what happens if the player drafted is 22 on the date of their first professional game, entering the league after their senior year in college. They are 26 when their rookie contract expires, and a four-year extension takes them until they are 30. Is there a great deal of value in locking them up to a third long-term contract?

Budgetary planning is vital for a general manager, and so many teams have great confidence in their own skill development staffs. Taking a younger player that needs growth in years one or two of their contract—but who will reap the benefits in year ten—is valued more than taking a ready-to-play senior that the team can only get seven or eight quality years out of.

None of this is rigid, but when spending millions of dollars on long-term commitments, we have seen a trend of younger players getting drafted earlier. It's not as much an indictment on their playing ability as how close they may be to their ceiling.

The inverse can also be the case: teams might need an immediate contributor late in the first round, and lack the commodity of patience. Age can dictate which type of player, and mature individual, they take.

9. The Most Crucial Data Points are Unavailable to the Public

Here's where things get tricky, and where I likely come off as a giant hypocrite.

The most important pieces of the scouting process take place behind closed doors and never reach the public eye: These are the conversations with college and high school coaches, the character references, the medical information and in-depth analytical studies that only a group with immense funding can undertake. Very few out there have the relevant information to make determinations on all this, and even if an outlet acquires that data on one prospect, there is no way to compare it to another.

What we do on internet outlets is make determinations based on the information we have. But we also must realize that our data points are inherently incomplete. We lack the staff—and often the league-wide access, even if we have team-specific contacts—devoted to in-depth analysis and digging of so many different avenues.

Take everything we provide with a grain of salt. The countless hours of work done by front offices is always going to have greater depth and contextualization than what we can provide here at The Box and One.

10. An Investment in Human Beings is Inherently Different

This is a team game. No individual wins a championship by himself or herself. Individuals are important, so we analyze their skill, their trajectory and the mesh of their talents in certain situations.

But what about understanding them as people? Statistics and scientific models move aside here.

Basketball is a business about people living up to their potential. There is no science for predicting who will and who will not, just an understanding that any investment in people is met with a certain level of unpredictability.

We hear buzzwords like maturity, character, chemistry and IQ all the time, but rarely give credence to how difficult it is to identify them. To go a step further, we rarely think about what they even mean.

If I'm an NBA general manager, I'm only selecting people that I trust to be on my team. Pressure and responsibility is high, and the right people are the ones that make the strongest impacts.

As Isiah Thomas once said, "The secret of basketball is that it's not about basketball".

A contract is as much an investment in a person as it is in their playing ability. Make sure you aren't overlooking the importance of the former in favor of the latter.