Coaches Corner: "We" and the Power of Intentional Language

Whether it's as a coach or a leader of any kind, emphasizing the collective need over your own has far more benefits than risks

“When I consider what tremendous consequences come from little things, I am tempted to think that there are no little things.” — Bruce Barton

Imagine sitting in a conference room as the member of a business team made up of seven members. The seven of you are before the CEO, here to simultaneously review your team and praise you for positive performance. The CEO has been impressed with your team’s production.

Your immediate supervisor, a man named Justin, is the one who brought the team together and helped organize the process, but the work done by the group took his vision above and beyond Justin’s control. He is also in the room with the CEO.

When the CEO and Justin go back and forth, Justin keeps making comments to the CEO about his team. “I’ll have my guys get on that change,” he quips right in front of the team. “I’ll have that on your desk by midnight tonight.”

You know what the veiled language really means: Justin will help organize the group before the team gets dismissed at 5pm. Then, he’ll go home and have a normal evening, waiting for an email in his inbox to simply forward onto the boss before the day is done. After all, his only job is to delegate.

When the CEO exits the conference room, Justin turns his attention to the group. “Alright folks — I need this done tonight, and done right. Joel, I need you to crunch the numbers. Alan, I have to see more passion from your written argument, it isn’t good enough. Don, my team is depending on you to finish this on a high note.”

Is Justin a poor leader of your group?

Not necessarily, though his usage of language could improve. By continually saying “I need” or “I’ll make this happen” in different iterations, he’s placing himself as the centripetal force of the team, inferring that “the result doesn’t get reached unless I’m involved” or “this is mine to take ownership of.”

Instead, Justin could replace “I” with “we”, placing himself as a part of the team and emphasizing the collective. How much of a difference does it make if he answers the CEO with “we’ll make that change” instead of “I’ll have my guys get on that?” What improves if he replaces “I need this done tonight” with “we need this done tonight?”

If you ask me, the change is vital for a team dynamic. After all, if I’m one of the seven members of the team, I’m not doing my job and striving for top performance for Justin, no matter what my relationship. There are intrinsic motivators (wanting to succeed because I care about my own reputation, not wanting to let the team down) and extrinsic motivators (I’ll receive more notoriety, recognition or reach different incentives if goals are met) at play. But Justin’s role in making that happen is fairly minimal.

Consider what a change in verbiage might do to team morale — or at least not to harm it. Teams work best when a sense of collective responsibility is present: that every team member brings value, that the value is recognized by the team and its leaders, and a desire and care not to let the others on a team down. Singling out Justin has above this dynamic and holding special position strains the group dynamic by default.

In basketball, this is a major emphasis of how we work with our coaches (notice the omission of “how I work with my coaches” there). The inculcation of this language — the collective over the individual — is meant to place the needs of the team over the needs of me, its coach. Inspiration for development and purpose for why our assistants work hard isn’t for their leader but for themselves and each other. It removes my ego from the equation as much as possible, which sets a positive example for the sacrifices we’ll expect from our players: it’s easier for them to think less about themselves when individualism isn’t modeled for them.

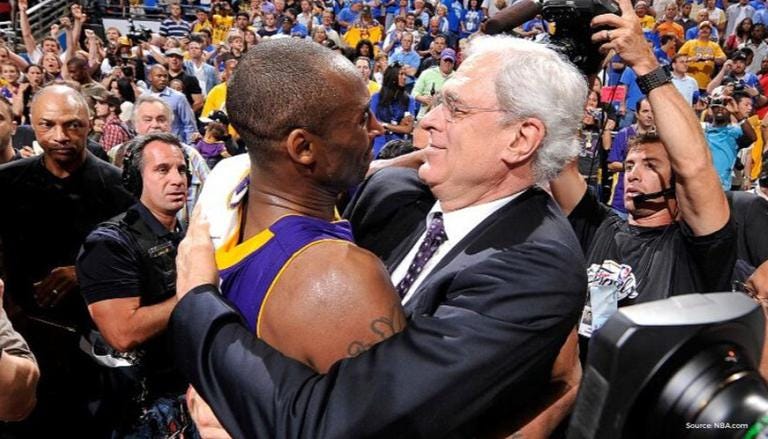

Most importantly for players, collective language always frames their improvement through the lens of what is best for the team, not for the coach or any single person. Developing a mindset for every member of the organization to do what is best for the team instead of themselves is ultimately is more appealing when sacrifice or change is involved. Listen to how many times Doc Rivers and Phil Jackson use the terms “we” or “us” throughout a game day:

This dynamics takes place in many arenas. My college coach was fantastic as using “we” instead of “me”. A fellow member of an athletic department I coached in greatly struggled and never used the term “we”. To some, this language is innocent and its effects minimal. But as coaches, we thrive on winning the details, the little things that matter. As author Bruce Barton once said, “when I consider what tremendous consequences come from the little things, I am tempted to think that there are no little things.”

As a result, we echo this language as much as we can: in our writing, in our daily life, all over as a means of training for when the team is listening. Since 2012, we’ve referred to the articles coming from The Box and One as “we” when appropriate — not to give the guise that there are multiple writers, but to avoid developing ego by constantly saying “I wrote this” or “this was my project.” Winning the details takes practice.

All coaches who read this are encouraged to take a similar path and find ways, when applicable, to speak in a collective voice instead of a singular one. Plenty have already spoken about the benefits of such an emphasis on their program.

For the NBA draft heads looking for evaluation points, yes — we spend time looking at interviews in the public sphere to see who only speaks in the first person, who tries to operate from a team perspective. That can be a mighty challenge when questions are so directed towards the individual, but a respondent who intentionally brings their answer towards a team mentality will look for other ways to do so in the pros.

Sift through those canned responses of “I’ll do whatever the team needs of me” and try to get to “we were up 5 with a minute to go and we needed the ball in our best free throw shooter’s hands, so I functioned more as a screener.” Hopefully we can spot the difference.